On the lamb

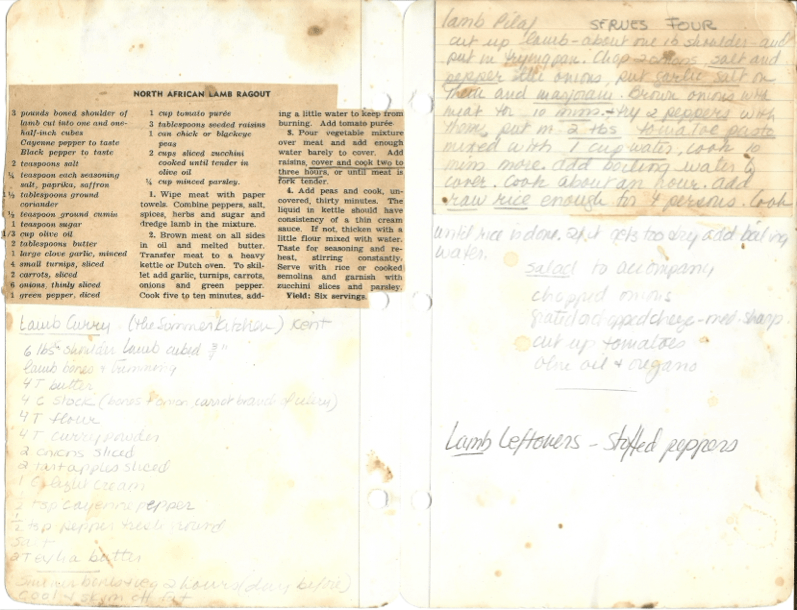

When my grandfather passed his apartment was quietly pillaged. As my family poured over old pictures and loaded furniture into their cars, I found myself holding his recipe binders. Organized alphabetically, they were filled with newspaper cutouts, glued to ringed pages with notes scribbled in the margins. In addition to all of the recipe binders I ended up with his cream colored KitchenAid from the 50’s, a Coupe De Ville in my eyes, complete with a meat grinder attachment.

My grandfather was full of contradictions – he stood at six and a half feet tall, yet never weighed more than a buck seventy five at any point in his life. He was a quietly devout catholic with a cheery inner peace who married a nonbeliever with serious anxiety. But what was most at odds was that his childhood and young adulthood took place during the Great Depression and WWII, yet he was both an unusually good cook and an oddly warm presence.

Throughout my dad’s childhood my grandfather didn’t cook. The meals my dad remembers sound more like British bar snacks than expressions of culinary creativity. The kinds of things you could sooner pave a road with than attempt choke down. According to my father he took to cooking in his retirement, and my dad showed a playful resentment whenever he would pick me up from their house to find I had fresh baked cookies. The only reason I’d heard of scrapple or chipped beef and crackers was thanks to my dads haunted memories. Yet, without training or a deeper cultural reference point to tap into, he regularly made elaborate holiday meals with little assistance.

The first five pages of my grandfather’s “Meat, L-Z” recipe binder are devoted to lamb. Gravies, pilafs, roasts, and ragouts, but his most infamous dish was roast lamb for Easter Sunday. My dad dreaded eating it more than any processed pork loaf from his childhood. My clean cut Catholic cousins made the trek to our neighborhood, and my family put on the niceties of the holiday we hardly celebrated. If my grandfather was still around today and serving it, I’d be sure to shoot my dad some quip about the suffering of Jesus or something. At the time, I was just excited to sneak away and drink Coke in the basement. My parents had rightly embargoed soda access back then, as I had rampant undiagnosed ADHD.

His Easter lamb recipe called for a simple rub of salt, pepper, dried rosemary and thyme and was supposed to be roasted for 30 minutes per pound. Even then I understood that creative liberties were being taken there. I now know there is a preamble in the recipe about how lamb is often overcooked in American cuisine, and my grandfather took this as gospel. The result is flavorful, but bloody. By the time it was passed down the long table it had a slight chill. The salt hadn’t had time to penetrate the thick slab of meat. I was a curious 8 year old, but not that curious. My parents’ doctrine of staunch politeness, which usually forced me to stifle any feelings I had about an unsavory task, had devolved into personal panic. The reality of choking this down was causing them considerable grief, as if this was their first Easter Sunday. We all load up on side dishes as a form of bargaining, my dad oscillates between anger and depression, it’s a quiet catastrophe. Every year the scene is the same, cousins slyly spitting copiously, optimistically chewed lamb into napkins alongside mostly untouched adult portions, all while my grandfather ate helping after helping, the rest of us looking on in disbelief.

Luckily, for occasions such as these there is a note in the binder that reads, “Lamb leftovers: stuffed peppers”.

My adult culinary relationship to lamb revolves mostly around cones of al pastor or shawarma, but I love lamb and a challenge. This past Christmas I wanted to rewrite history, and I’m naive enough to think that I can do it with a single dish.

My mother, ever my culinary accomplice, quietly bought the lamb and under cover of darkness I prepared it for roasting. I wanted something strong enough to tamper down the lamb-ier aromas and interesting enough to reshape the traditionally scarring Easter dish. I settle on a chaotic mix of tomato and anchovy paste, lemon zest and thyme, with enough garlic and Calabrian chilies to make someone’s Nonna proud.

Finally, nestled among yellow cherry tomatoes, wedges of red onion, and sprigs of herbs, the lamb awaits its larger purpose as a revisionist dedication to the deceased. I start roasting it early in the morning, so that when people notice I’m cooking, it smells of roasting allium, herbs and browning meat, not the unsightly butchering of the animal most closely associated with innocence.

Dinner time comes and the lamb is resting on the counter, browned and aromatic. Family filters through the kitchen on the way to their seats. They look excited, and tell me how delicious it all looks, as if we had never spat the remnants of a long past lamb into our napkins. It may be adorned with fresh herbs and sizzling in a way that indicates inner doneness and warmth, but it largely looks the same as my grandfathers.

It occurs to me how much good will I’ve built up in the service of this meal. Yellowfin ceviche at the beach, peking duck, fresh ravioli, countless 11th hour turkey carvings. Part of me wonders, if I had undercooked this how much would I find in the napkins? Cooking is about trust, and trust is a two-way street. So for whatever reason these folks trust me to cook them lamb, despite our collective gastronomic trauma and for that I am not going to check the napkins.

I’ve added one last note to the margins of the “Meat L-Z” binder, “Don’t skimp on the seasoning, don’t undercook lamb shoulder, and don’t squander the goodwill cooking affords you”.

Leave a comment